By Jessica Dawson

Special to The Washington Post

Sunday, June 18, 2006; N01

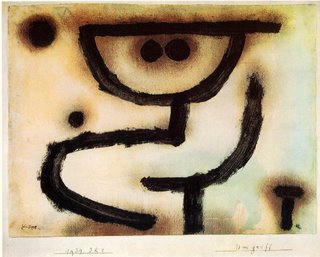

A Paul Klee exhibition in the United States is bound to prompt a question:

What, exactly, does a Paul Klee painting look like?

We Americans aren't likely to know. Although the Swiss-born artist's fame came easily enough in Europe -- where his career flowered in the decades before his death in 1940 from scleroderma -- those on this side of the Atlantic missed the memo itemizing Klee's talent and influence.

Perhaps that's because the artist never traveled stateside and never really wanted to. Perhaps Americans didn't cotton to Klee's jittery lines, off-note color schemes and childlike surrealism. Or maybe his reputation as a fringe-dwelling visionary turned people off.

"Klee and America," on view at the Phillips Collection, offers alternate explanations for our country's slow warming to the idiosyncratic painter. This nation, after all, did accept him, although the embrace was warmest after his death.

The artist's American market witnessed its first uptick toward the end of his career, when his reputation in Europe soured due to Nazi interference. In the early 1930s, he benefited from the efforts of a strong cohort of expatriate American dealers who pushed his work stateside -- and by the middle of that decade, his work found Americans sympathetic to his talent and his persecution.

Later in the 20th century his impact was clear, but it's been 20 years since Americans saw a major Klee show. If we struggle to conjure a Klee in our minds, perhaps we can be forgiven our fuzzy-headedness.

The nearly 80 works in "Klee and America," organized by Houston's Menil Collection, serve as a barometer of the artist's rise in this nation's consciousness during his lifetime. Only those paintings and works on paper that landed on U.S. soil are on view.

Tracing Klee's relationship to the United States through the pictures Americans bought is an unusual curatorial tack, one that scholars might delight in viewing. For the everyday museum visitor, though, the exhibition performs a more urgent task: It shows us what Klee's pictures look like.

"Klee and America," it should be noted, is no survey. Only 10 percent of Klee's output is held by Americans, so this show registers the tastes of a discrete collecting population. The accompanying catalogue, a 315-page behemoth that's richly illustrated and thoroughly researched, parses the details of transatlantic Klee transactions and the early-20th-century tastemakers who brought his work here.

We learn about Katherine S. Dreier, who in the 1920s founded Societe Anonyme in collaboration with Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray and organized Klee's first one-man show in the United States, in 1924. We learn that six years after that, Alfred Barr -- a man whose reputation requires no further gilding -- mounted the largest solo show of Klee's work outside Europe, at the Museum of Modern Art; Klee was the first living European artist to receive a solo show there. Also found in the catalogue's pages: The notion that Klee didn't gain traction here until his fortunes fell in Nazi Germany.

You'll have to crack the catalogue to get the details. The Phillips exhibition is mercifully free of didacticism. "Klee and America" asks us, quite simply, to look. And we've got some excellent pictures from the 1920s and '30s to feast on.

Many of Klee's pictures were made in Germany, where he spent most of his life. After moving to Munich at the turn of the century and abandoning a career as a concert violinist (he would continue to play all his life), he began painting lessons. Klee and Wassily Kandinsky, himself fresh from a career change, shared painting instructor Franz von Stuck, an artist specializing in the macabre themes of late symbolism and art nouveau.

Although Kandinsky and Klee shared a belief in the spiritual nature of art and its eruption from deep human drives, their work took very different forms.

Although Kandinsky and Klee shared a belief in the spiritual nature of art and its eruption from deep human drives, their work took very different forms.When Klee worked in abstraction, as he did in "Gradation, Red-Green (Vermilion)," a 1921 watercolor on view at the Phillips, he never approached Kandinsky's bravado of color and scale. Klee's exercise in color and composition is much more intimate and subdued than any Kandinsky. Most of the Klees here are the size of postcards or notebook paper. (A few get larger as he approaches his final years. Most suffer a little for it.)

Although Klee lived in Germany, a strong strain of French surrealism ran through his pictures. The twitchy lines and oddball creatures of Klee's works from the 1920s show why the French considered him one of the fathers of dada. At the Phillips, the Duchampian "Twittering Machine" is on view, as is the anxiously Freudian "Girl With Doll's Pram," where the little girl's breasts are the size of Hindenburgs.

For most of the 1920s, Klee taught at the Bauhaus and later at the Dusseldorf Academy. But his time in Germany ended badly. His teaching emphasized individualism, and the Nazis found his lessons suspect, dismissing him from the Dusseldorf position in 1933. Several years later, Germany exhibited some of his most childlike work in its degenerate-art exhibition. Klee spent his final years in exile in Switzerland.

Klee's waning European fortunes offered more opportunities for Americans to acquire him. In "Klee and America," wall labels detailing provenance read like small-scale society rags. That the picture called "Plan of a Castle" (a spatial exercise in floating polygons) belonged to Philip Johnson in the years 1948 to 1961 comes as no surprise, given the architect's taste for geometry. That Johnson also owned the childlike ink drawing "Not Without Heart" (1928) -- in which Klee renders a dachshund out of a parallelogram with charming naivete -- seems rather out of Johnson's character. (A few years later, the collecting stars realigned when the piece turned up in gimlet-penned draftsman Andy Warhol's cache.)

Among the Important People who acquired Klees was Duncan Phillips. Visitors to this leg of "Klee and America" get a special treat: a re-creation of the Klee room that Phillips maintained for nearly 40 years, beginning in 1948. In a former sewing room on the second floor of the museum mansion, 13 tiny Klees hung shoulder-to-shoulder for the enjoyment of thousands of visitors, Kenneth Noland and Mark Rothko among them.

That little group, perhaps the strongest subset of "Klee and America," reminds us what fun Klee is, and what peculiar attraction his works offer.

That little group, perhaps the strongest subset of "Klee and America," reminds us what fun Klee is, and what peculiar attraction his works offer.Although the museum plans to rehang the Klee room after "Klee and America" ends, the when and where of that arrangement remain uncertain. For the time being, at least, our chance is now.

Klee and America at the Phillips Collection, 1600 21st St. NW, Tuesday-Saturday 10 a.m.-5 p.m., Thursday 10 a.m.-8:30 p.m., Sunday noon-5 p.m., through Sept. 10. $12 adults, $10 age 62 and older and students. Free to those 18 and younger and museum members. Call 202-387-2151 or visit http://www.phillipscollection.org/ .

posted by follower of basho

No comments:

Post a Comment