Pablo Picasso on a beach in 1937.

I found this essay on Picasso dealing with Picasso's sexual imagery of himself as a Bull man, and Hitlers assertion that artist who paint` unusually' should be castrated so as not to pass down the genes. Interesting.

Hitler's resolve to castrate modern artists only strengthened Picasso's obsession with the bullish minotaur, writes Robert Nelson.

.

Picasso did paint one direct commentary on war, his mural-sized Guernica from 1936; but this famous picture is the exception that proves the rule.

For the rest, Picasso's pictorial agonies seem to lack a moral or political frame and, instead, you get a great sense of an artist proud of his masculinity.

I've always felt that the image of the weeping woman in Picasso proceeds straight from the artist's ego. The spectacle of female pain and vulnerability flatters the artist's power and boastful privileges - at the expense of female gratification - of exercising an imaginary superhuman potency.

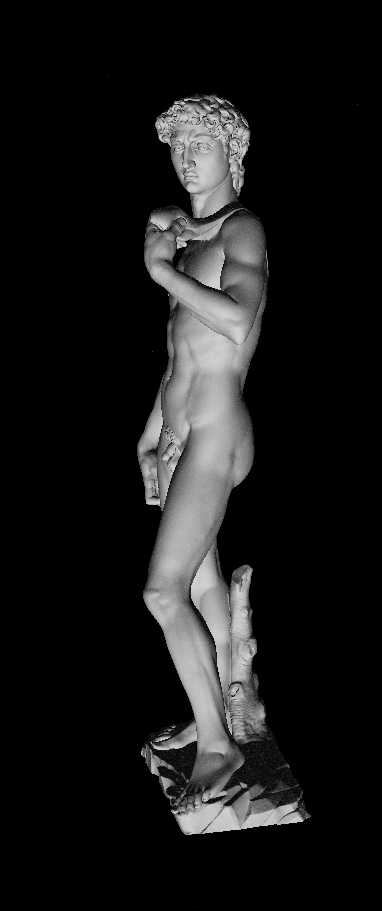

For years, Picasso identifies with the image of the minotaur and once went so far as to describe the bull-man archetype as analogous to himself. This mythical creature is conveniently revived from ancient Greece as a grandiose pretext for showing off; for it allows Picasso to hang upon the human frame the formidable head and testicles of a bull.

What kind of courage did it really take Picasso to advertise his randy instincts? How can his manifest indulgence - supported by an establishment of collectors and museums - be construed as an act of resistance?

Never was ancient myth so prostituted in the service of an artist's delusion, and never were such fantasies turned so successfully to the marketing of conceit and the pomposity of genius. How can we celebrate all that big-headedness, especially when transacted in an age of mass extermination?

The Picasso exhibition at the NGV has made me rethink some of those claims to which previously I'd given no credence. It is a serious study of the relationship between Picasso and his volatile lover and model of the war years, Dora Maar, an interesting artist in her own right.

Anna Baldassari is more than the curator of the current exhibition; she's also the author of a learned monograph accompanying it. Among many fascinating historical explorations, this eloquent book introduces some chilling facts concerning the culture of the German occupation in which Picasso was domiciled.

In Picasso's library, Baldassari found a volume of a magazine (Lit tout) summarising Hitler's policy on art. It described a strategy so unsettling that I decided to check to see if the report on Hitler's plans was really true. So I hunted down the 'Urtext' to find a loathsome document that is predictably painful to read. This awful exercise proves the truth of the account that Picasso would have read in Lit tout.

In 1937, Hitler gave the inaugural address at the opening of the "Haus der deutschen Kunst". This was a defining moment in Nazi cultural history, launching not only the severe neo-classical building by the architect Paul Ludwig Troost, but announcing what kind of art should go into it. The only profession for which Hitler had any training was art; he had a special interest in controlling it and approached it with a vengeance.

Hitler's philosophy of art is much as you would expect. He hates modern fads and fashions; he wants to see eternal greatness and absolute beauty, as of the Greeks, beyond time and transcending the happenstance and contingencies of the epoch. Art should aspire to universal virtues and beauty.

These tenets, structurally speaking, are the same kind of essentialist aesthetic still pursued by some writers today who denounce the relativism of critical theory in contemporary art. But Hitler's diatribe against modern art isn't just an expression of scorn and contempt, such as conservatives rehearse still today.

By 1937, Hitler was not merely venting his frustration but redesigning the world to his plan. Just as he was determined to eliminate Jewry and homosexuality from Aryan dominion, so he was prepared to stamp out, by whatever means, the congenital sickness that expressed itself in modern art.

Towards the end of his somewhat reasoned speech, Hitler comes to the crunch. In regard to the distortions and perversions of modern art, he declares:

"There are only two possibilities: either these so-called 'artists' really see things in that way and believe in the (appearance of) things that they represent, in which case it would only remain to investigate whether their ocular failure has arisen in a mechanical way or through inheritance ('Vererbung').

"In the one case, it is deeply sad for these unfortunate ones, in the second, important for the Ministry for the Interior, which would then have to concern itself with the question of how, at the very least, to prevent ('unterbinden') further inheritance of such a ghastly disturbance of vision."

In other words, the most conservative or minimal treatment of the degenerate artists is to ensure that they don't have children, lest their congenital shortcomings are transmitted to another generation. Sooner or later, Hitler was going to have the balls of the avant garde; and Picasso's would have been close to the top of the list.

An artist facing the threat of sterilisation would have no recourse to excuses along theoretical lines to do with illusion and perspectival experiments. Hitler's next sentence excludes this appeal: "Or, however, they do not themselves believe the reality of such impressions, but are motivated by other grounds, to annoy the nation with this humbug, whence such a process falls into the area of the criminal justice system (Strafrechtspflege)."

The artist would be tried in court, I imagine, for subversion, the punishment for which would probably be the death penalty. Nazi culture was not compassionate and ultimately saw all forms of cultural difference in congenital terms. No artist could assume that these guys were joking. They were serious about deleting unwanted lines of defective progeny. You wouldn't have imagined that you could somehow laugh it off. If you were deemed degenerate, you feared the worst.

The report in Picasso's possession explains that Hermann Goering had given "instructions for carrying out artistic cleansing to the civil servants of Germany's fine arts institutions" with "the order to act without pity against all the partisans of modernism". Indeed, pity and Goering had no overlap and resisting compliance with his edicts would have been nigh suicidal.

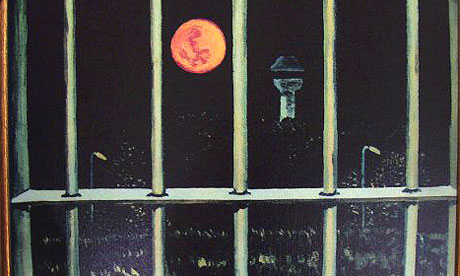

Quite what it felt like in those years to be a modern artist in the occupied territory (1940-44) is hard to imagine. The urge to make radical pictures would not have been encouraged with the triumphal jubilation that it enjoys in hindsight, and the terror of cultural oppression would have weighed heavily on the brush. There's no doubt that painting in a non-illusionistic way would have required a brave spirit.

The circumstances covered in Picasso: Love & War 1935-1945 are exceptional and horrendous. But apart from inspiring some humility among us postmoderns in relation to Picasso's creative torment, the dark recesses of history help connect two qualities in tension within the pictures: one, a kind of ballsy swagger and the other cry for freedom, especially using the female model.

The case shouldn't be overstretched. After all, Picasso was painting somewhat similar pictures before and after the period of the Vichy government; and the Nazi threat of castration would have had no influence. So it would be unhistorical to see Hitler as somehow conditioning the imagery or the intention behind any of Picasso's pictorial innovations, subject matter or expressive habits.

The audacity that made Picasso archetypical is a condition all to do with art and personality; it isn't primarily directed against the fascists in Spain or Germany. But the authoritarian mood in Europe that grew explosively with Franco, Mussolini and Hitler had a much longer lead-time than just the later 1930s, and modern art adopted an unmistakably anti-authoritarian posture in relation to mass conformity and agreed symbols.

The period was also obsessed with origins, the racial origins of people and their psychology, their assumed character, culture and even physical traits. As well as totalising the diversity of people, the fascination in cultural origins followed a master-narrative of racial purity. Picasso, though not necessarily chauvinistic in this regard, somewhat shared the disposition.

In the cubist period (early 20th century), Picasso was interested in space and composition, using motifs such as jugs, mandolins and figures. But from the 1930s, the intellectual concerns of the cubist years receded in favour - certain sentiments more closely identified with the Latin patrimony. Picasso turned to the dark mythical strata that might propose some kind of explanation for the enduring rituals and psychology of the Mediterranean.

The bull, which is still a fetish in Spain through bloody rituals, is explored in relation to Greek myth, likewise steeped in genealogies and procreative sacrifices. Baldassari sees the obsession as being primarily about art: "This symbol of the Minotaur, this man-bull Picasso chose as the emblem of his own persona, is moreover the very figure of myth, and thus an expression of the possible that is the condition of art."

But I think this return to the archaic is more about a common stock of culture. Specifically, the figure of the minotaur is also about "kinds of men". Heroes. Men of original nature who are imagined with enormous bollocks and, consequently, all the metaphors of courage and sexual vigour that go with them.

And so it seems that in this epoch, the bollocks go full circle. As the seat of male genetic material, they're at once tossed to the audience as a trophy of the artist/lover and solicited by the fascist dictator who wants to control them and snuff their wanton sprog. Gratefully, I guess, there is another phase, where the genetic resources swing gleefully back into boastfulness and produce more modern progeny that recuperates the same ancient animal vim.

In our more modest epoch, this bizarre emphasis on manly prowess strikes us as repugnant in greatly different measures, but on all sides a bit disgusting.

It has also contributed to the persistent cultural conceit that it takes balls to make modern art. In this economy, you'd have to ask: what chance did Dora Maar have?

robert.nelson@artdes.monash.edu.au

Picasso Love & War, is on at the NGV International, 180 St Kilda Rd, until October 8.