The New Yorker: The Talk of the Town

The New Yorker: The Talk of the Town:

THE 40-MILLION-DOLLAR ELBOW

Issue of 2006-10-23

Posted 2006-10-16

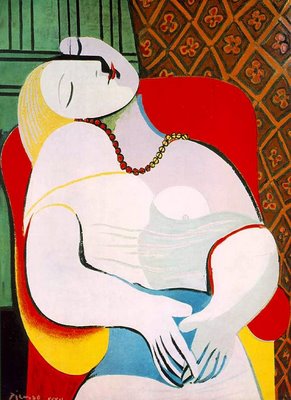

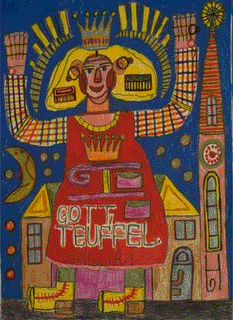

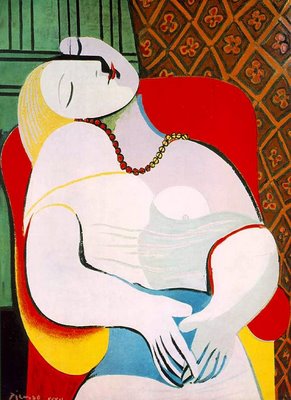

You might have seen “Le Rêve,” Picasso’s 1932 portrait of his mistress, Marie-Thérèse Walter, in your college art-history textbook. The painting is owned by Steve Wynn, the casino magnate and collector of masterpieces. He acquired it in a private sale in 2001 from an anonymous collector, who had bought it at auction in 1997 for $48.4 million. Recently, Wynn decided that he’d like to sell it, along with several other museum-quality paintings he owns. A friend of his, the hedge-fund mogul and avid collector Steven Cohen, had coveted “Le Rêve” for years, so he and Wynn and their intermediaries worked out a deal. Cohen agreed to pay a hundred and thirty-nine million dollars for it, the highest known price ever paid for a work of art.

A few weeks ago, on a Thursday, a representative of Cohen’s came from California to inspect the painting. She removed it from the wall, took it out of its frame, and confirmed that it was in excellent shape. On Friday, she wrote her condition report, and so, according to their contract, the deal was done. All that was left was the actual exchange of money and art.

That weekend, Wynn had some friends visiting from New York—David and Mary Boies, Nora Ephron and Nick Pileggi, Louise Grunwald, and Barbara Walters. They were staying, as they often do, at his hotel and casino, the Wynn Las Vegas. As they had dinner together on Friday night, Wynn told them about the sale. “The girls said, ‘We’ve got to see it tomorrow,’ ” Wynn recalled last week. “So I said, ‘I’ll be working tomorrow. Just come on up to the office.’ ” (He had recently moved “Le Rêve” there from the hotel lobby.)

The guests came at five-thirty, and Wynn ushered them in. On the wall to his left and right were several paintings, including a Matisse, a Renoir, and “Le Rêve.” The other three walls were glass, looking out onto an enclosed garden. He began to tell the story of the Picasso’s provenance. As he talked, he had his back to the picture. He was wearing jeans and a golf shirt. Wynn suffers from an eye disease, retinitis pigmentosa, which affects his peripheral vision and therefore, occasionally, his interaction with proximate objects, and, without realizing it, he backed up a step or two as he talked. “So then I made a gesture with my right hand,” Wynn said, “and my right elbow hit the picture. It punctured the picture.” There was a distinct ripping sound. Wynn turned around and saw, on Marie-Thérèse Walter’s left forearm, in the lower-right quadrant of the painting, “a slight puncture, a two-inch tear. We all just stopped. I said, ‘I can’t believe I just did that. Oh, shit. Oh, man.’ ”

Wynn turned around again. He put his pinkie in the hole and observed that a flap of canvas had been pushed back. He told his guests, “Well, I’m glad I did it and not you.” He said that he’d have to call Cohen and William Acquavella, his dealer in New York, to tell them that the deal was off. Then he resumed talking about his paintings, almost, but not quite, as though he hadn’t just delivered what one of the guests would later call, in an impromptu stab at actuarial math, a “forty-million-dollar elbow.”

A few hours later, they all met up for dinner, and Wynn was in a cheerful mood. “My feeling was, It’s a picture, it’s my picture, we’ll fix it. Nobody got sick or died. It’s a picture. It took Picasso five hours to paint it.” Mary Boies ordered a six-litre bottle of Bordeaux, and when it was empty she had everyone sign the label, to commemorate the calamitous afternoon. Wynn signed it “Mary, it’s all about scale—Steve.” Everyone had agreed to take what one participant called a “vow of silence.” (The vow lasted a week, until someone leaked the rudiments of the story to the Post.)

The next day, Wynn finally reached his dealer, and told him, “Bill, I think I’m going to ruin your day.” The first word out of Acquavella’s mouth was “Nooo!” Later that week, Wynn’s wife, Elaine, took the painting to New York in Wynn’s jet, where she and “Le Rêve” were met by an armored truck. Cohen met them at Acquavella’s gallery, on East Seventy-ninth Street, and he agreed that the deal was off until the full extent of the damage could be ascertained. The contract, at any rate, was void.

The painting wound up in the hands of an art restorer, who has told Wynn that when he’s done with it, in six or eight weeks, you won’t be able to tell that Wynn’s elbow had passed through Marie-Thérèse Walter’s left forearm.

Last Friday, when Wynn’s alarm went off, at 7 A.M., his wife turned to him in bed and said, “I consider this whole thing to be a sign of fate. Please don’t sell the picture.” Later that morning, Wynn called Cohen and told him he wanted to keep the painting, after all.

— Nick Paumgarten

MORE : THE TALE TOLD BY SOMEONE WHO WAS THERE: NORA EPHRON (From Huffington Post )

Nora Ephron

My Weekend in Vegas

We got there Friday night and went straight to dinner at the SW Restaurant, which is of course named after Steve Wynn. I'd never been there. It has a strip steak that I honestly thought was the finest steak of my life, and let me tell you, I eat a lot of steak. (This reminds me, someone at our table ordered a steak made of grass-fed beef, it was the second time I'd had grass-fed beef in less than a week, it's become a big trend, and may I say that someone should stamp out grass-fed beef because it has no taste whatsoever.) Anyway, while we were eating, Steve and Elaine Wynn stopped by the table. Wynn was in a very good mood because, he told us, he had just sold a Picasso for $139 million. I was surprised he'd sold it, because the Picasso in question was not just any old Picasso but the famous painting Le Reve, which used to hang in the museum at the Bellagio when Wynn owned it, and no question it was Wynn's favorite painting. He'd practically named his new hotel after it, but at some point in the course of construction he'd changed his mind and decided to name the hotel after himself, which, when you think of it, was a good idea, what with the homonym and all. Meanwhile, he named the Cirque de Soleil Show at the Wynn after Le Reve.

The buyer of the painting, Wynn told, was a man named Steven Cohen. Everyone seemed to know who Steven Cohen was, a hedge fund billionaire who lived in Connecticut in a house with a fabulous art collection he had just recently amassed. "This is the most money ever paid for a painting," Steve Wynn said. The price was $4 million more than Ronald Lauder had recently paid for a Klimt. Oh, that Klimt. It had set a bar, no question of that, and Wynn was thrilled to have beaten it. He invited us to come see the painting before it moved to Connecticut, never to be seen again by anyone but people who know Steven Cohen.

The next day, after an excellent lunch at Chinois in the Forum Mall, which is the eighth wonder of the world, we all trooped back to our hotel to see the painting. We went into Wynn's office, which is just off the casino, past a waiting area with a group of fantastic Warhols, past a secretary's desk with a Matisse over it (a Matisse over a secretary's desk!) (and by the way a Renoir over another secretary's desk!) and into Wynn's office. There, on the wall, were two large Picassos, one of them Le Reve. Steve Wynn launched into a long story about the painting -- he told us that it was a painting of Picasso's mistress, Marie-Therese Walter, that it was extremely erotic, and that if you looked at it carefully (which I did, for the first time, although I'd seen it before at the Bellagio) you could see that the head of Marie-Therese was divided in two sections and that one of them was a penis. This was not a good moment for me vis a vis the painting. In fact, I would have to say that it made me pretty much think I wouldn't pay five dollars for it. Wynn went on to tell us about the provenance of the painting - who'd first bought it and who'd then bought it. This brought us to the famous Victor and Sally Ganz, a New York couple who are a sort of ongoing caution to the sorts of people who currently populate the art world, because the Ganzes managed to accumulate a spectacular art collection in a small New York apartment with no money at all. The Ganz collection went up for auction in 1997, Wynn was saying -- he was standing in front of the painting at this point, facing us. He raised his hand to show us something about the painting -- and at that moment, his elbow crashed backwards right through the canvas.

There was a terrible noise.

Wynn stepped away from the painting, and there, smack in the middle of Marie-Therese Walter's plump and allegedly-erotic forearm, was a black hole the size of a silver dollar - or, to be more exactly, the size of the tip of Steve Wynn's elbow -- with two three-inch long rips coming off it in either direction. Steve Wynn has retinitis pigmentosa, an eye disease that damages peripheral vision, but he could see quite clearly what had happened.

"Oh shit," he said. "Look what I've done."

The rest of us were speechless.

"Thank God it was me," he said.

For sure.

The word "money" was mentioned by someone, or perhaps it was the word "deal."

Wynn said: "This has nothing to do with money. The money means nothing to me. It's that I had this painting in my care and I've damaged it."

I felt that I was in a room where something very private had happened that I had no right to be at. I felt absolutely terrible.

At the same time I was holding my digital camera in my hand - I'd just taken several pictures of the Picasso - and I wanted to take a picture of the Picasso with the hole in it so badly that my camera was literally quivering. But I didn't see how I could take a picture - it seemed to me I'd witnessed a tragedy, and what's more, that my flash would go off if I did and give me away.

Steve Wynn picked up the phone and left a message for his art dealer. Then he called his wife Elaine. "You'll never believe what I just did," he said to her. From where we stood, on the other end of the phone call, Elaine seemed to take the news calmly and did not yell at her husband. This was particularly impressive to my own husband. There was a conversation about whether the painting could be restored - Wynn seemed to think it could be - and of the two people in America who were capable of restoring it. We all promised we would keep the story quiet - not, you understand, to cover it up, but to make sure that Wynn was able to deal with the episode as he wished to until it came out. We all knew it would come out eventually. It would have to. There were too many of us in the room, plus all the people in the art world who were eventually going to hear about it.

Meanwhile, we were not going to tell anyone.

We promised.

I promised.

That night we went to dinner, once again at SW because that's how great it is, it's worth going to two nights in a row. They were serving creamed corn with truffles, which was amazing. Once again the Wynns joined us. They were in a terrifically jolly mood, all things considered, and Wynn told us that he planned to tell Steve Cohen the next day that of course Cohen was released from the deal because the painting had been damaged.

After dinner I threw eight or nine passes at the craps table, one of which included a hard ten.

The next day one of my sons came to meet us in Las Vegas, and we went to Joe's Stone Crab, which is excellent, and where the key lime pie may be even better than the key lime pie at Joe's Stone Crab in Miami Beach, if such a thing is possible. I told my son the story of what had happened to the painting, but it didn't really count because my son is completely trustworthy.

Nine days passed and I told no one else. It was the most painful experience of my life. But I felt good, too, because, as I say, I knew the story would come out eventually and when it did, I didn't want it to be my fault. And the story did come out.. Ten days after Wynn put his elbow through the painting, there was an item about it on Page Six of the New York Post. It was very clear who had given Page Six the item, and it wasn't me. I was thrilled that I had managed to keep the story (more or less) to myself and celebrated by calling several friends and telling them my version of what had happened.

Two days later, I got a call from a reporter at the New Yorker who said he was going to write a piece about the episode. I still didn't feel comfortable discussing the event, but I called Elaine Wynn and told her the New Yorker was going to write a story and that Steve should call the reporter back and tell him about it, since no question the story was out there.

Elaine told me that she was glad I'd called because she had awakened that morning with the realization that Steve's putting his elbow through the painting had been a sign that they were meant to keep the painting. So they were going to.

Now, in today's New Yorker, there's a very charming piece about the incident, and as far as I'm concerned I am entirely released from my vow of silence on the matter.

So there it is.

My weekend in Vegas.