A Silenced 'Scream' Haunts Art Heist Trial

Six men in Norway face charges in the theft of Munch's masterpiece, which is still missing.

By Jeffrey Fleishman, Times Staff Writer

This is a follow up to an earlier post:

The

Scream Stolen

Oslo — They whirled past portraits and Impressionist nudes, masks pulled tight, chrome-plated .357 Magnum flashing, visitors scattering for cover, highbrow chatter turning to fear. The men stopped at the painting of the willowy figure with hands to his face, his mouth agape in bewilderment.

"The Scream" was ripped from the wall. The gloved thieves turned to another Edvard Munch masterpiece. "Madonna," her head tilted, her hair black and tousled in a way that is at once erotic and spiritual, was yanked from her silver cables.

The paintings were heavier than the men had anticipated. They struggled as they hustled out the museum's glass doors. A metallic-black Audi shimmied to life and roared away, speeding up a hill, pieces of pine frames blowing out the window, leaving a trail of splinters in the street. The car stopped near a train trestle. The paintings were shoved into another car; the Audi was sprayed with a fire extinguisher to smother fingerprints and traces of DNA.

The heist at the Munch Museum was executed minutes before lunch on Aug. 22, 2004, a warm Sunday in the land of the midnight sun. Today, snow falls across Oslo. It flickers outside the second-floor courtroom where six men accused of stealing Norway's national treasures stand trial. The state rested its case last week, and verdicts are expected soon.

Police have amassed 70,000 phone taps and surveillance tapes, but there's an air of incompleteness to the proceedings. Like a murder case without a body, the paintings have not been recovered. They were last seen wrapped in black plastic and rolled in carpets, stored in a bus near a barn.

"We do not know where they are," prosecutor Terje Nyboe said.

Munch limned the subconscious, sought the darkness. He once said he was born dying. But even he could not have reckoned that his work would disappear into a rough underground of robbery clans in this Scandinavian land where automated teller machines get blown up, gangs go by the names of Torpedoes and Bandidos, and thieves with tattoos running up their necks answer to aliases such as the Dog, the Beard and the Spirit.

Not even a genius of such dour demeanor could have imagined that his iconic vision of existential angst would be stolen not to grace the wall of a sinister collector, but, prosecutors believe, to divert attention from another crime — a $10-million heist four months earlier from the Norwegian Cash Service center that left one police officer dead and pierced a country the United Nations often describes as the best place in the world to live.

Enter crime boss David Toska. The aura, if not the presence, of Toska permeates the Munch trial. A pudgy-faced man in his 30s whose e-mail identity is Superstar, the onetime national chess competitor turned purveyor of sledgehammers and automatic weapons was sentenced to 19 years in prison this month for masterminding the break-in at the cash center known as Nokas

The robbery set off Norway's biggest manhunt; police say that while Toska was on the lam he ordered his crew to snatch the Munch paintings to draw the heat somewhere else.

"This crime lacked sophistication. It was not the work of fictional French thief Arsene Lupin with his tuxedo and white gloves," said Jorunn Christoffersen, the museum's communications director. "The paintings were stolen by bank robbers who deal in narcotics and weapons. Art is not their field. It seems they have no link to the art world dealers of new rich Russians and eccentric Americans."

Judge Arne Lyng sat impassively in his high-back chair the other day, fidgeting, chewing on a pen and listening to lawyers and the defendants at the heart of the case: Stian Skjold, a man with spiky brown hair and a tattoo who police say was one of the robbers; Bjorn Hoen, a wiry man with a shaved head and a previous robbery conviction accused of planning the theft; and Petter Tharaldsen, a compact man with a goatee charged with driving the getaway car.

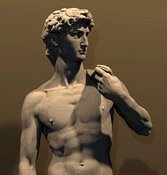

Actual picture of the theft

Actual picture of the theftThe heist was classic smash and grab. Two men — one in a hooded gray sweatshirt, the other dressed in black — overpowered four unarmed guards, terrified 80 visitors and escaped with two priceless paintings. The guard at the museum entrance thought the robbers might have belonged to a neighborhood youth gang out to cause trouble. That assessment abruptly changed when one of the men held the Magnum to a woman's head.

The museum alarm was hit at 11:10 a.m. Police didn't arrive for about 15 minutes. By then, the getaway car was gone.

"The Scream" and "Madonna," according to police and witness testimony, were stashed on the farm of Thomas Nataas, a race car driver. Police say Nataas has connections to criminal elements, but he says that he was competing in Germany when the paintings were delivered. Surveillance led police to the property the night of Sept. 24, 2005 — more than a year after the crime. But when two cars left the farm, police tailed the wrong one. The paintings vanished into the darkness and the police were again criticized for blowing the case.

That missed opportunity gnaws at Nyboe, the prosecutor. He has a stern face, as if cut from ivory, and blue eyes that can look at you a long time before they blink. He once served on Oslo's SWAT team and went to night school for a law degree.

Nyboe doesn't believe the pictures have appeared on the black market. Several art dealers and at least one industrialist have offered to buy the stolen Munchs and return them to the museum. Police officials suggest that Toska may attempt to barter the paintings for a shorter prison term in the Nokas heist.

Hoen's lawyer, Morten Furuholmen, has wavy, sandy-blond hair and a smile that invites conversation. He's a legal celebrity, a young, eloquent tactician who sometimes draws a subtle smile from the judge. He said it was a tragedy the police had not recovered the pictures. He quickly added that his client was the wrong man.

"Yes, Hoen knows Toska," Furuholmen said. "But Hoen was not involved in Nokas. That's why it's a bit strange for him to be accused of being the 'general' in the Munch robbery. Why should Toska rely on him? They have no criminal history together."

The Munch paintings are ghost exhibits in this drama, their images flashed occasionally on the courtroom slide projector. But the judge, lawyers and defendants know the gravity of what has been lost. It is as persistent as the snow. This is a small country, and Munch and playwright Henrik Ibsen represent its grandest artistic achievements. "The Scream" is Norway's contribution to the quiet fear and angst of the human spirit, a painting as recognizable as the "Mona Lisa."

Munch described the inspiration in his diary: "I was out walking with two friends — the sun began to set — suddenly the sky turned blood red — I paused, feeling exhausted and leaned on the fence — there was blood and tongues of fire above the blue black fjord and the city — my friends walked on, and I stood there trembling with anxiety — and I sensed an endless scream passing through nature."

Munch painted four versions of "The Scream." One of them was stolen from Norway's National Museum of Art at the opening of the 1994 Winter Olympic Games in Lillehammer. It was a bumbling caper that included a thief tumbling from a ladder and a note left for the museum: "Thanks for the poor security." The painting was recovered months later in a sting operation.

That heist seemed from a more whimsical time, before Norwegian gangs toted submachine guns and collaborated with Balkan and Albanian criminal organizations that deal in heroin, hashish, bank robberies and killing. Police have made numerous arrests in recent years but estimate that 30 to 50 hard-core robbery gang members remain at large.

The walls in the courtroom of the Munch trial are the color of corn silk. Lawyers wear black robes. Some of the accused smile; others are more taciturn, reading documents, whispering asides.

One is quite nervous. A bulletproof vest bulky under his sweater, Petter Rosenvinge, yet another Norwegian underworld figure with a shaved head who admits he's done some bad things, is in a predicament. He's accused of selling the getaway car to Hoen. He's also been cooperating with police while trying to keep a healthy distance between his name and the word "snitch." Hoen eyes Rosenvinge like a linebacker waiting for a halfback to dart through the wrong hole.

To listen to Rosenvinge on the witness stand is to marvel at how sentences can be coolly turned into mazes. He talks about evidence not being burned, chances being missed and about the "boys in Oslo being tailed." When pressed, however, he says such meanderings are hypothetical, things he could imagine but not necessarily know because, after all, "How could I know?" When phone taps featuring his conversations alluding to the heist are played, he tells Nyboe in his best Tony Soprano: "Sometimes I get a little overenthusiastic."

The snow was still falling when two school buses arrived outside the Munch Museum on a recent morning. With backpacks and mittens, the children looked to be about 8 or 9. They waited in line and grew perplexed as they stepped through thick sliding-glass doors, a metal detector and the gaze of security guards. The museum has spent about $6 million on security and other measures since the paintings disappeared.

"The politicians would have laughed if we would have requested money for protection against armed robbers before the 'Scream' and 'Madonna' theft," said Christoffersen, the museum's communications director.

She swiped her ID card and followed the route of the robbers, pointing out other security measures: a guard box, cameras dotting the ceilings, two gates that could trap thieves and a labyrinth of walls that allows visitors to snake past pictures while making it difficult for potential criminals to navigate.

Christoffersen stopped at the wall where "The Scream" once hung, looking as if she had lost her wallet on payday.

She spoke of splintered frames and broken glass and how a visitor from the U.S. on the day of the robbery identified the gun as a Smith & Wesson .357 Magnum.

"He said, 'I'm from Texas and I know what kind of gun that was,' " she said. "Of course, we wouldn't have known such things, but I suppose a man from Texas would."

She turned and walked through another set of sliding doors that led back to the foyer, where snow whirled against long windows.